January 2017 - Rebecca Harding, Economist, provides a Trade Outlook....

The picture for global trade in 2017 is uncertain and likely to be dominated by the Politics of trade rather than the Economics....

The year promises to be an exciting one for us. With Donald Trump's inauguration, and Article 50 triggering the Brexit process, both in Q1, we are expecting the politics of trade to be at the centre of public discourse. Here are our initial thoughts on the outlook in 2017 and we look forward to sharing more with you during the course of the year.

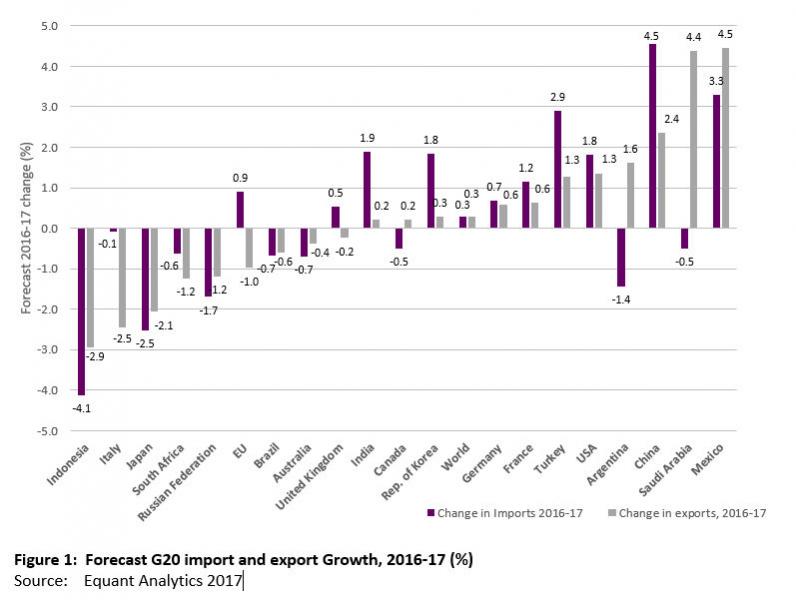

The picture for global trade in 2017 is uncertain and likely to be dominated by the politics of trade rather than the economics. We are expecting values in world trade to increase in 2017 by less than 0.3% with 12 out of the G20 countries set to see either exports or imports, or both, shrink during 2017 (Figure 1). While we are expecting China’s exports to grow at over 4% this year, this is a long way from the heady days of 2010 and 2011 when trade grew at twice the level of GDP.

|

In the wake of the Brexit referendum, the UK’s exports are expected to see flat or negative growth in 2017. Similarly, imports are expected to increase only slightly. This is simply a function of the weaker sterling pushing export prices down and import prices up, but it sends a worrying signal for economic performance more generally as the effects of Article 50 are felt and broader uncertainty around investment begins to take hold. |

Politics will dominate 2017, not economics

Can 2017 be as dramatic as 2016? Probably not, although suddenly the economics of uncertainty has become popular in public discourse. The truth is that nobody knows what will happen - except that we don’t know. As an economist, this is a real challenge: uncertainty means that we cannot make assumptions with any degree of robustness. And if we can’t make reasonable assumptions, then orthodox forecasting tools are rendered useless.

This is not just a challenge for economists, of course. Any consultant, or analyst, will be facing the same challenges. As a result, many are looking at what they do know about 2017. Here are my thoughts on the key things that will affect bank performance during the course of this coming year.

First, the economics. 2017 is certain to be a year in which interest rates in the US start to “normalise.” President Trump has made it clear that he wishes to boost infrastructure spending and re-focus US economic policy on wealth creation and jobs within America. The Fed is already set on a gradual path to push up rates for the year and we can expect three, maybe even four hikes. Alongside this, the planned fiscal expansion is likely to lead to higher inflation and this will determine the speed at which the Fed has to hike. A gradual approach to returning rates to normal may not have much impact on markets or policy elsewhere, but if the Fed is compelled towards the end the year to put up rates by increments that are greater than 25 base points, this could have consequences for Central Banks in other countries too.

Second will be the Article 50 trigger. Last year UK politicians discovered the need to be guarded about what they said about Article 50 and Brexit to avoid a sterling flash crash. Some argue that markets are less volatile. However, this does not mean that they are not nervous and this is arguably because of the political risks that will be endemic. Article 50 may catalyze another drop in sterling although it signals only the start of discussions. What it will do, however, is set the UK on an uncertain path driven by the forces of politics rather than the forces of economics.

These political forces in the European context are well-rehearsed. The Brexit vote may well have catalysed anti-establishment sentiment in Europe; and the outcome of elections in the Netherlands, France and Germany during the course of the year will determine the future structure of the EU just as much as Brexit itself. How the ECB deals with Italian banks and the issues that still surround Greek debt will be important too.

Third, Donald Trump’s victory has created a major shift in policy from globalization to Americanization. This is not about economics – it is deeply political with trade finance and trade negotiations likely to be profoundly affected as new US negotiating stances unravel. The US has already signaled the likelihood that it will pull out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and shift its trade relationships with China in favour of America. The Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) appears dead in the water on both sides of the Atlantic and is unlikely to move anywhere given Brexit and both European and US reluctance to move ahead. Ironically, it may well be China that benefits: it has moved already to create Asia-specific trade partnership in which it is the central player.

The consequence of all the political uncertainty will be more economic nationalism and more regional, multi-lateral agreements as the trade system readjusts to the shifting tectonic plates underneath it. Trade growth has slowed dramatically in the last few years, and there is no sign of any speedy recovery under current uncertainties. Add to this the geopolitical risks in the Middle East which may continue to impact both trade and oil prices during the course of the year, and China’s shift in trade focus towards Russia and Iran and away from the US, as a likely product of US strategy, appears sensible.

The fallout of political uncertainty will be in trade, whose growth is already slowing globally. This has profound implications for the way in which the global economies operate and how global economic growth is driven. 2017 will be a defining year for the world – not because of the economics, but because of the politics.

Liveryman Dr. Rebecca Harding

Co-Founder and CEO

Tel: +44 (0)7803 710711

Email: rh@equant-analytics.com

Twitter: @RebeccaAHarding

Skype: rh.equantanalytics