...relying almost entirely on the expertise and judgment of one individual...

Obvious names come to mind, like Churchill deciding that Britain would never surrender, Stalin making Stalingrad the anvil on which to hammer the Nazi Sixth Army, Truman dropping the H-bombs, commanders of armed forces, or Denniston who created Bletchley Park. The list goes on.

All these people had time and cabinets, staff, and advisers aplenty to help them make the decisions. But who, with a team of just a handful which was scattered far and wide, made the most momentous decision in hours if not minutes – relying almost entirely on his own expertise and judgment and with a huge weight of lives, military success or failure, and political triumph or disaster at stake?

The Run-Up to D-Day.

It was originally planned for 5th June. To mount the invasion, commitment had to be made two days before. Battleships in Scapa Flow had to sail south. Tens of thousands of troops had to be brought from bases to the ports and embarked on the landing craft etc. Airborne missions had to be set up.

Eisenhower, his deputy Tedder, and various commanders like Monty and Bradley were advised by a small group of meteorologists. From early spring Eisenhower had asked for three day forecasts to gauge their reliability.

At 21:30 on 2 June the leader of the group was due to make his report to Eisenhower and his top D-Day officers.

The leaders of the Liberation of Western Europe. From the left: Bradley, Ramsey, Tedder, Eisenhower, Montgomery,

Leigh-Mallory, Smith

The meteorology head first spoke over the ‘phone to his team in different locations. There were that day indications of worsening weather in the Atlantic but no consensus among the team about what it meant. The sun was shining and the sky was clear (double summer time for those who thought they’d spotted - Agatha Christie-like - a slip in the story!). He hurried to the meeting and followed his own instinct – “The whole situation from the British Isles to Newfoundland had been transformed in recent days and now is full of menace”. Several officers looked out of the window in bewilderment. Eisenhower probed about 6th and 7th June. He was told “I would be guessing, not behaving as your meteorological advisor” [a very professional approach that many today might do well to mark!] This was a huge call for a subject expert on his own in august company, and knowing how much materiel, and how many men, ships, and aircraft were poised for 5 June.

He left the room. After a while a staff officer came out to say there would be no change of plan at least for the next 24 hours.

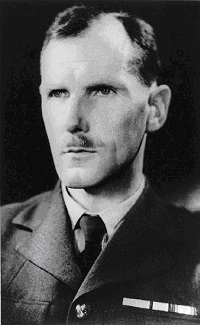

Dr James Stagg

Who was he?

The team leader was Dr James Stagg, given the rank of Group Captain to lend him the necessary authority in a military milieu. He had been superintendent of Kew Observatory.

A Development

Early the next morning, 3rd June, a weather station in western Ireland reported a rapid drop in pressure. At 2130 Stagg presented himself to Eisenhower again. ” The fears we had yesterday for the next 3 or 4 days have been confirmed.” He presented a gloomy picture of rough seas, force 6 winds and low cloud. This meant a debilitating passage across for the troops; no air cover for the ships and on the beaches; and a threat to the parachute attacks. Despite fine weather outside, Eisenhower felt compelled to order a postponement. Stagg didn’t sleep, but wrote up his notes of discussions. The weather was calm all night.

Why had 5th June been chosen? That night it would be a full moon with spring tides, and at dawn it would be mid-tide, best disclosing obstacles, and rising during the day. If the attack didn’t happen in a narrow window of three or so days the next window would be two weeks later, with a vastly increased risk; the secret would get out and the Nazis could reinforce Normandy.

At 0415 on 4 June Eisenhower held another conference and he agreed the postponement must stand. Convoys were called back. Destroyers raced out to round up landing craft that had not acknowledged the recall radio signal.

Urging The New Opportunity

By the evening of 4th June, the team had noticed that the Atlantic depression had concentrated, but slowed down in its eastward track. At the 2130 conference with rain and wind battering the windows, few felt optimistic. But Stagg said that “since I presented the forecast last evening some rapid and unexpected developments have occurred over the North Atlantic. There would be a brief improvement from afternoon of 5 June.” Weather not ideal but it would do.

And so D-Day was on 6 June and took place in decent conditions.

What a call!

In making his weather forecast James Stagg took the most momentous decision made by an individual.

Edward Sankey, Past Master

I am pleased to acknowledge Sir Anthony Beevor and his excellent book “D-Day- The Battle for Normandy” for the information. Likewise, United States Government for the SHAEF conference photograph and Wikipedia for information about James Stagg and the portrait https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Stagg

This account was first delivered as part of a talk to the WCoMC Wine Club trip to Sicily. It started as a talk about Mediterranean winds and their effect on the Second and Third Crusades. Don’t ask.